What is it about making things with our hands that provides so much satisfaction? Why are we so drawn to the archetype of the craftsman? In his insightful book, Why We Make Things and Why it Matters, furniture builder and woodworking instructor Peter Korn explores the philosophy of craftsmanship. In the podcast today, I talk to Peter about the ethos of craftsmanship, what craft can teach us about living the good life, and why you should get out in the garage and try building something with your own two hands.

Show Highlights

- The definition of craftsmanship

- How our idea of the archetypal craftsman was created in the 19th century

- Why building with our hands is so satisfying

- What we really buy when we buy a hand-built product from a craftsman

- What craftsmanship can teach us about living the good life

- And much more!

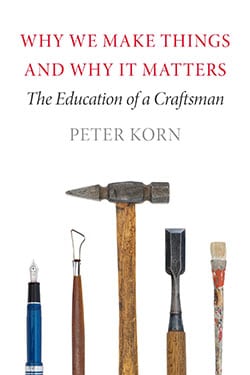

Why We Make Things and Why It Matters is a fantastic treatise on the nature and philosophy of craftsmanship. It’s a great addition to the library of books on the topic, including Shopclass As Soulcraft and Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Even if you’re not a craftsman, you’ll get insights on how you can live your life more thoughtfully and creatively.

Listen to the Podcast!

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Download this episode.

Follow us on SoundCloud.

Subscribe via iTunes. (Please give us a review if you enjoy the podcast. It helps others discover us.)

Follow us on Stitcher.

Special thanks to Keelan O’Hara for editing the podcast!

Read the Transcript

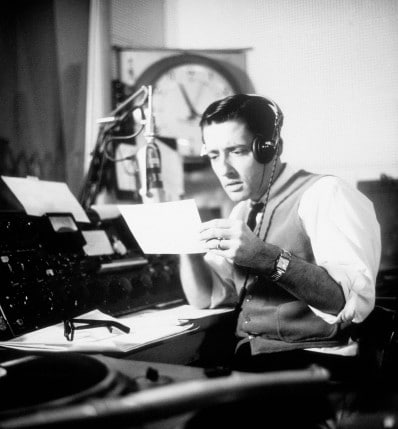

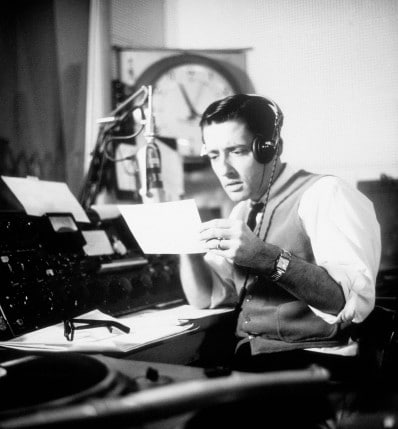

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. This idea of craftsmanship and the archetype of the craftsman I think is something very attractive. It resonates with us on a visceral level of us. There’s something about building things with our hands from scratch that just is satisfying and there’s something that were drawn to. We’d rather buy something that we know was made by hand by a craftsman than some manufactured mass produced goods. Why is that? Why is that we have that attraction to building things, why is it that we attract this idea of craftsman.

Our guest today has written a book exploring that idea. He’s an actual craftsman, he makes furniture. He also founded this furniture-making school in Maine. His name is Peter Korn, and he wrote a book called Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman; fascinating book on a fascinating topic. Today on the podcast we’re going to discuss what’s this drive in us that gives us satisfaction to build things with our hands. We’re also going to talk about what craftsmanship, this will be the ethic of craftsmanship, can teach us about living a good life, a fantastic discussion, really fascinating, delve deep into some deep topics. I think you’re going to like this, without further ado Peter Korn on Why We Make Things and Why It Matters.

Peter Korn, welcome to the show.

Peter Korn: Thank you Brett. Thank you very much.

Brett McKay: You are a furniture maker who happens to write, can you tell us how you got started into furniture making because this whole … I think this idea when you started at least there really weren’t a lot of independent furniture makers. How did you get into that?

Peter Korn: I was fortunate enough to go to a Quaker High School in Philadelphia, Germantown Friends School, which I think is a great education and then go to the University of Pennsylvania where I studied history but all that … and I graduated from college in 1972 so I was sort of 60s hippie kind of guy, and all the time I was in school I felt like I was living like second hand and real life must have been somewhere else. When I finished college what I did was I took a job as a carpenter on the Island of Nantucket which at that time was a very quiet forgotten place not the bustling plutocracy that it is today.

I had never worked with my hands, and I came from a background where my father was a lawyer and my mother was a historian, and they didn’t know anyone at least socially who worked with their hands, and then their world working with your hands would really take you down the social ladder, so my father at least was pretty horrified that I took a job as a carpenter. I took that job only because I moved to Nantucket because I wanted to live in this rural beautiful place and that was the first job that came along. Much to my … The life full and pleasant surprise that I found out how rewarding and challenging carpentry was. If I may continue …

Brett McKay: Sure, yes,

Peter Korn: My father was quick to say … He was just worried that with a work like that my mind was going to be undeserved. It was going to really be a truncated, that means short and that’s not the right word.

Brett McKay: Stifled.

Peter Korn: A stifled sort of life, however you want to put it, mentally stifled. I found that carpentry engages your cognitive problem solving skills for example to a huge extent. Your brain is involved as well as your hand and I found that sort of work a wonderful way to grow into adulthood at the age of 20.

Brett McKay: How did you go from carpentry to designing furniture, that sort of a leap?

Peter Korn: It’s a little bit of a leap but wooden tools are involved. After two years as a carpenter … When I was in the carpentry for about two years and was gaining some sort of confidence in my hand, some friends of mine were expecting a child, and this was my first friends who were expecting a child, and I wanted to make a cradle for them. Three days before the baby was due I took some pine and some dolls from the lumberyard, went into this unheated barn at the end of November where I froze my butt off, and built a cradle from a picture I’ve seen in a book.

I went into that barn thinking that I was going to end up designing and building houses for a living and I walked out of the barn just passionate to rediscover what seemed … at that time 1974 like the lost art of furniture making. This was before fine woodworking came out or all the other woodworking journals that have been around now for decades. Then there was almost nowhere where you could formally learn fine woodworking in this country. There were two places you could go to, the North Bennet Street School or the Rochester Institute of Technology but I was completely unaware of them. I’ve never met a craftsperson.

For me it was like trying to learn this craft and rediscover it for myself just from a few books published in England and it turned out there were … I thought I was doing this in isolation and I was but at the same time there were probably thousands or tens of thousands of other people in this country of my generation turning to various crafts in the same ignorant way because we were looking for lifestyles that would be more seamless and fulfilling than what we perceived our parents world presenting to us.

Brett McKay: Let’s go to that question. I think when people hear the word craftsman, this I do this at least and they imagine sort of the sturdy industrious independent man in his workshop with a beard probably leather apron, rolled up sleeves, salt to the earth, and it’s an archetype I think and it’s very attractive to people and it’s also … it has become almost just like platonic ideal of what a craftsman is, but you make the case in your book that this idea of the craftsman that we have sort of romantic idea is a fairly recent creation. Can you tell us about the arts and crafts movement, the 19th Century.

Peter Korn: I’d be happy to. The place to start is to realize that in totally industrial revolution which essentially took place between the late 1700s and late 1800s, everything was made by individual, by an individual by hand what we would today say by hand and nothing was mass produced. There was no assembly line. There was no power-driven machine except for water-driven threshing mills or whatever, grinding mills. There was no need to even have a concept like craft when everything was craft and then what happened as the industrial revolution came along and I’m now speaking about Europe specifically and even more specifically England. Suddenly the trades where you work by hand many of them were displaced by manufacturing and so craftsmanship became redundant.

By the late 1800s that process had gone a long way and there were people in England particularly John Ruskin and William Morris are the two most familiar names who were very concerned as I guess the social philosophers that the conditions of labor in manufacture were really demeaning to the workers themselves, bad for them spiritually and bad for them morally, and that if workers, if the work was bad for the workers and it was deleterious to their character that was bad for society, so they invented the idea of craft as an alternative methods of making things where the worker would be fully engaged in the full process and ink the quality of what they do because that would be more spiritually and morally beneficial to the worker and therefore society. Before they invented craft, before the arts and craft or even invented craft in English the word “craft” did not mean a type of object or a method of fabrication as we think of it today.

The word “craft” was used meant what we now hear in coinages like witchcraft and statecraft which is to say an ability to manipulate people or situations cleverly. They invented this idea of craft and their craftsman was someone’s employee who would build someone else’s design through from start to finish in the healthy environment. That idea there is that is what you just described which has come down to us to the state, this hallmark card like image of the craftsman as a skilled tradesman securing the knowledge of his hand and the strength of his character, come at the workbench hand pursuing a simple peaceful life and idyllic surrounding.

For my generation we’d now liking the craft almost a 100 years after they came up with this idea of craft that idea was there unconsciously because I’d never thought about craft but at the same time there was this whole overlaying of new ideas about craft that those guys, Ruskin and Morris wouldn’t have recognized. Do you want me to go on?

Brett McKay: Yes. What did that new movement bring to the craft?

Peter Korn: For my generation what we very much saw craft as was an opportunity to be self-employed, self-expressive, self-sufficient and self-actualized. The obvious common word there being self, and thinking about this I then came to see that between the end of the 19th Century and the late e part of the 20th Century which is where I was practicing craft for the most part. The normative idea in our society of what an individual is, of what the self is, had changed radically. It had been changing a long time but it really changed quickly and radically in 20th Century, and the difference was that for all of human history the individual had thought of himself or herself as belonging to a larger social entity as sort of conceptualize the self you might say it’s like a finger on the hand.

In the 20th Century we saw the rise of this idea of the individual as being fully autonomous and separate and individual and rational, and able to choose everything was choice, and instead of belonging to a society being shaped by it we started to see ourselves as being to pick and choose where in society we want, what ideas we like, and it was that idea of the fully autonomous individual that changed the way we approached craft so that another way to say this is that if you look at art over the millennia, art just tend to portrait a place where they think truth resides and so you’ve got a Greek Art portrayed this ideal of humanity outside of space and time in other words truth lay outside of humanity.

You’ve got a lot of Christian art in the middle ages and the renaissance that portrayed scenes from the bible essentially, the idea being the truth resided in God’s kingdom, in the bible, as you know it’s expressed in the bible, again, outside of man. And then you’ve got the Hudson River School of Art in the 20th Century which portrayed nature and that went along with all sorts of enlightenment idea about the novel savage and so truth was thought to reside in nature, and then if you come into the 1940s for example our abstract expression as in you’ve got artist who are splattering paint or they’re painting abstract things where the panting take shape because every choice the artist makes is a response to whatever previous mark he or she has made on the canvas. Every choice the artist makes is a response to whatever previous mark he or she has made on the canvas, and so what you get as people painting a portrait of their intuition, of their interior self, so that we were out of place then where truth resides internally and it’s for us to discover as artist or as an individuals and bring forth to share with other people to very different concepts of what the individual is that has shaped my generation and subsequent generations.

Brett McKay: We’re talking about craftsmanship, and this is a topic that sort of is woven throughout your book, that ideally what is craftsmanship, because I think people have rough notions of it, what they imagine what craftsmanship is, but I think if you ask different people you’ll probably get different answers on what craftsmanship is.

How do you define craftsmanship like when does something become … you’re displaying craftsmanship whenever you’re doing something.

Peter Korn: I have to offer two definitions of craftsmanship.

Brett McKay: Okay.

Peter Korn: One is, craftsmanship if you’re talking about within the world of craft themselves where people are fabricating objects out of actual physical materials, and if that’s where we’re looking to define craftsmanship then we’re talking about, if craftsmanship is work or a work process that engages hands kills yet it requires developed skills, it requires an on wavering commitment to quality and also a heightened understanding of one’s materials. Those are the three elements that go into craftsmanship that are common to craftsmanship.

Then you could think about craftsmanship when for example people will talk about a lawyer crafting of a brief well or manufacturers talk about the craftsmanship in their automobiles for example. Now, we don’t have individual agencies involved, that’s been removed. We don’t always have physical materials involved but we still talk about craftsmanship and what remains there is that that implies a commitment to quality and a deep understanding of one’s materials even if one’s materials are worst or something that’s doesn’t have any physical materiality. This is caring about what you do, commitment to quality, deeply understanding one’s material. Those are the elements of craftsmanship in general.

Brett McKay: Why do you think it’s … What is it about building with your hands though that helps you get in touch with that idea of craftsmanship more so than a lawyer crafting a contract., what is it about the materiality of craftsmanship working with your hands that allows you to get in touch with that.

Peter Korn: I think there’s actually several ways to describe that and I’m actually … I think I’ll try three of them.

Brett McKay: Sure.

Peter Korn: One of them is that there’s an experience that create the people having this studio, in this case it could be craft, it could be paintings, sculpture, it can be writing in fact that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi if that’s the proper way to say his name who wrote a book called, “Flow” and some other books on this topic. He labels that this phenomenon flow where you disappear, your sense of time and self all disappears, yourself fully engaged in the work that that’s all there is and that turns out to be an immensely pleasurable wonderful feeling.

Create a people you could almost say enjoy their creativity or come to it simply for that feeling but there’s a lot more to it but that is one element. What’s wonderful about craft in addition to that is that you can’t … how to say, it anchors your creative work, your ideas and your efforts substantially in the real. For example when I’m writing, writing you can put words together and it can suggest new ideas and you can go off and flight the fancy that are quite seductive but they actually maybe called nonsense.

But when you’re working with wood and chisels for example, there’s no question about whether a joint is tight, there’s no question about whether a chisel is sharp. In fact, there is no question about a chair is comfortable by just apparent to any user. Your ideas, your suppositions, your efforts are checked by the real, and that’s actually quite a healthy thing. That’s one of the pleasures of craft. Another is that at the end of the day you see what you have achieved. It exist in the physical world to be enjoyed, shared with others, it does just disappear off on the computer screen on to the next thing. At least those are some of the things that made craft such a delightful thing to practice.

I’ll have one more.

Brett McKay: Go ahead, yes, it’s fantastic.

Peter Korn: There is this maxim in craft that Bernard Leach, a British Potter is said to have stated back in the last century which is that craft engages head, heart and hands in unison, he said it a little better than that. That is I think one of the things that makes it so fulfilling is that you are somehow when you’re engaged in skilled craft work, and let’s say you’re in the state of flow of not, it doesn’t really matter, you’re employing all of your bodily, all of your human capacities at once. You’re engaging your actual physical capabilities, you’re engaging your imagination, you’re engaging your ability for cognitive problem solving. And you’re engaging your creativity. And you can ask for more than that.

Brett McKay: You’re right, you mentioned how you found when you first started carpentry you found that it not like what your father said, it would sort of dull the mind that it actually engages the mind. I’ve had that experience too when I’ve done sort of projects around the home. It’s amazing how much harder a little project, the DIY project that I’m doing is then saying writing an article for the website is, and how fun it is. There’s a challenge there, and you’re not going to stop until you solve it. You just keep plugging at it even though I should have given up hours ago.

Peter Korn: Right, you see Brett for me the shoe is on the other foot meaning I’m used to solving problems in the woodshop and so that becomes a fairly smooth process for me but when I sat down to write this book all I started with were certain deeply held convictions that were almost more physical, to sort of convictions you hold and this pivot your stomach and your bones then I had ways of expressing them with words. For me working with words was a process of trying to untie knot, one knot after another.

It was a long engaging, deeply engaging struggle that was wonderful and I’ve write before work and then I’d be driving to work and I have to pullover to jot down the next little step front idea that as it unfolded itself that was wonderful.

Brett McKay: Here’s the question I had so right now it seems like we’re having a renaissance in the marketplace where handmade goods, artisanal things are hot. Everyone wants something that’s … They want something that’s build by a craftsman, they want something that they know is not made by a giant corporation or a machine, but the 20s is that you can buy a table that was built in a factory and it’ll be an exact same table built by a single person. But then people will probably pick the one that was built by the person. Why is that?

Peter Korn: You have just so hurt the feelings of that individual person. I just want you to know that.

Brett McKay: I know, but what is it that a person is buying, so I guess this is the way of the third person to taking part in the creative process. What is it that we’re buying when we purchase something built by a craftsman. Is it a story, is it a sense of meaning, what is it?

Peter Korn: Yes, it’s all those things. You’re buying … First of all, I’m going to disagree or rephrase something that you said which is this that if you were engaged and trying to make your living as a furniture maker for example you would find that in fact it’s really hard to find the market for your work that the more skill you put into it the more expensive it get, the smaller your audience becomes. In fact, as my observations that my generation of crafts people … I’m going to say this differently, I belong to … retrospectively is now labeled a movement called studio craft and studio crafts people made one of a kind singular objects that existed as ways for them to develop their individual artistic voice and their individual skills and show them off and I mean that in a positive way. Those end up being fairly expensive gallery pedestal objects.

Young people who were excited about designing and building things today for the most part aren’t interested in making those precious gallery style objects, there’s a whole new movement that is sort of centered in Brooklyn that I called studio design. People are still designing and building wonderful things but these are meant to be things that can be produced by others at more reasonable price points and sold to a wider audience and there are other concerns like sustainability and community that somehow enter their design process as well, so sort of the cultural reasons to which people work have changed and that changes the nature of the object.

I think the object younger crafts people or these product designers that everyone say are making today actually are probably more marketable and have more of a market than those of my generation but they’re best products they’re not the one of a kind thing. Still to answer your question what sells them is the fact that they’re authentic, that they did come from one person’s imagination and one person’s caring about their quality, and that is the story that has to be told otherwise it doesn’t … no one would know that so yes, you could say it was the product of the piece having a story.

Brett McKay: One of the things I love about this book is that you talk about craftsmanship and the drive to build them, why is it so fulfilling, but you also explore how the journey of to becoming a craftsman is also a journey on how life should be lived which is very Aristotelian in a way. Aristotle talked about virtues, the practice of virtues sort of like practicing being a craftsman of some sort.

How can craftsmanship help us or studying craftsmanship help us live a good life?

Peter Korn: That brings the question what is a good life, and I guess that is the largest context within which I’m writing is trying to answer that question, and it seems to me based on my experience and observation that a good life is one that provides the person living it with a sufficiency of meaning and fulfillment, those seem to be the two qualities we’re so hungry for so often seem missing today and I have come to define meaning as having a sense that your thoughts and actions actually make a difference in a larger moral fear.

And I come to define fulfillment at least for myself as the sense that you are using your human capacities for the fullest. Practicing a craft is not the only way to achieve meaning fulfillment but it’s a wonderful way to do it. The fulfillment part comes as we discuss because in craft you really are employing head, heart and hand in unison. All reading form the same page, and in terms of the work giving you a sense of making a difference in a larger moral fear if I can just talk about furniture making for a moment, every piece of furniture describes the life to be lived around it if you think about it. So the work you would see at Riverside is very ornate, uncomfortable chairs, incredibly expensive, they are describing, there is a whole world of how you sat in the chair and how you relate it to other people and all that is described by those chairs, so say a rocking chair describes a whole another attitude towards life. The idea that daily life and work should be lived to sacraments, so when you’re designing furniture in a sense what you’re always doing is you are trying to more closely and ever more closely approximate through the furniture how one as a human being might best live their lives, what ones daily life should feel like that sort of thing.

That’s one example of how being engaged in a specific creative endeavor can be an exploration of how we should live as human beings and really in my mind and I’m not a religious believer so certainly from my point of view the largest moral context that exist is the effort of humanity over all of its existence, the ongoing effort to define what it is to be human and how we should live, and I think that anytime anyone engages in the effort of trying to bring something new into the world that matters not only to themselves but matters to other people they’re actually engaged in exploring the parameters of existing ideas of what it means to be human and how we should live and it’s the fact that in that larger context that gives their life meaning and in fact, I’m not saying anyone in the creative arts for example is ever conscious of that context or thinking about the ideas that I’m discussing, I’m just saying this is what I see as the underlying reality to all creative effort and not just creative effort in the paint or studio or the craftsman’s shop but creative effort in the science lab, creative effort in starting a new business, creative effort in trying, coming up with new recipe in your kitchen. These are all expanding the boundaries of how you think about the world and which means that you’re coming up with new ideas about who you are and how the world around you works.

Brett McKay: It’s fascinating, and you … we could talk more about this but time is limited and so I definitely recommend people to check out the book. Where can we learn more about your work?

Peter Korn: I have a website for the book which is peterkorn.com but really my real work in life has been founding and running a school called The Center for Furniture Craftsmanship, a non-profit school in Rockport Maine and the website for the school is woodschool.org and that’s what I’ve been doing for the last 23 years. I’m much more of … these days an art administrator and a teacher than I am an actual craftsman. I’m one of 40 plus people who teach at the school. That’s where you would really see and learn what I do and what I’m passionate about.

Brett McKay: Is the school open that they’re like, do you have classes for beginners, people who have never done furniture building ever?

Peter Korn: Yes, we have an extensive summer and fall schedule of one and two-week courses that many of which are entry level in furniture making but also in wood churning and in carving and other aspects of wood working and then we, the rest of the year we run a nine-month furniture making course and a bunch of three months long churning and furniture making courses which most people take because they want to become professional at it but that they are also open to and attended by many amateur woodworkers as well.

Brett McKay: Have you noticed as an interest in the school gotten bigger and bigger throughout the years or does it stayed about the same or?

Peter Korn: Well I started the school by teaching six people at that time in my backyard so I run seven to or maybe it was nine to a week workshops that first year and so the school went through a period of rapid and tremendous growth for the first six to eight years and now we have 400 students a year come through. But then in around the recession that happened in the early 2000s the woodworking world saw a cultural interest level of and now we’re seeing it grow again and we’re seeing more younger people come again and more people come again and that’s pretty exciting but again they’re coming in not necessarily from an interest in craft the way I pursued it but something that looks almost the exact same except for its informed by those, the newer world that younger people live in and perceived. As I said there’s great interest not only in fine craftsmanship and work that expresses your voice but there’s also an interest in having you design a wonderful product, a chair that can be made that’s affordable to others.

Brett McKay: Very nice. Peter Korn, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Peter Korn: Brett, thank you so much. I really appreciate you interviewing me.

Brett McKay: Our guest is Peter Korn, he’s the author of the book “Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman” You can find that on amazon.com. Go check it out it’s really fascinating to read. You’ll also find more information about Peter’s work at peterkorn.com and that’s Korn with a K and also if you’re interested in checking out the furniture building school that Peter founded and check out one of the classes that they have to offer you can find more information about that at woodschool.org, again that’s woodschool.org.

What wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this podcast and you’re getting something out of it I’d really appreciate if you go give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, whatever it is you used those on the podcast that I hope get the word about the podcast and I really appreciate that, so until next time. This is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.

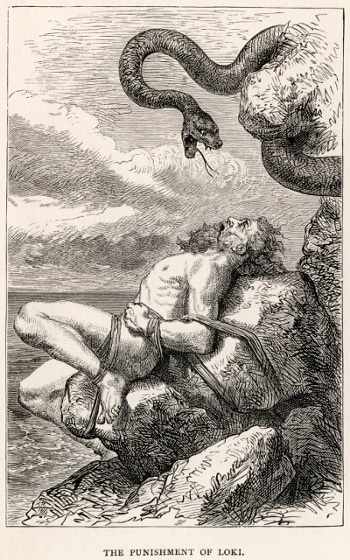

Loki then went out and found some mistletoe to bring back to Asgard. He approached the god Hodr, who was blind, and convinced him to take a spear and throw it at Baldur as yet another test of his invincibility. Indeed, the spear was crafted from mistletoe. Hodr threw the shaft, which pierced Baldur and killed him on the spot.

Loki then went out and found some mistletoe to bring back to Asgard. He approached the god Hodr, who was blind, and convinced him to take a spear and throw it at Baldur as yet another test of his invincibility. Indeed, the spear was crafted from mistletoe. Hodr threw the shaft, which pierced Baldur and killed him on the spot.